Wash your hands! You’ve heard it a million times by now. And most likely you’ll be hearing it millions more over the next few months.

During a global pandemic, washing your hands frequently goes a long way in protecting yourself and your loved ones. Done properly with soap and water, it can save lives.

But why soap? and what makes soap so effective against viruses and more importantly, against SAR-CoV-2?

Let’s find out.

What is soap?

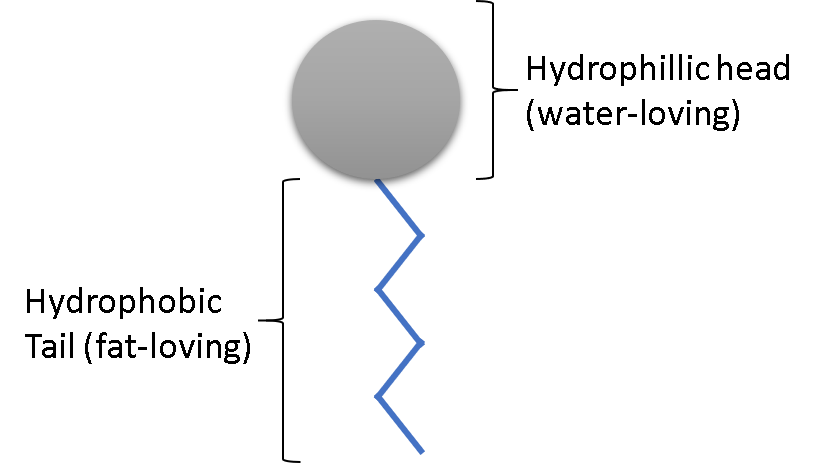

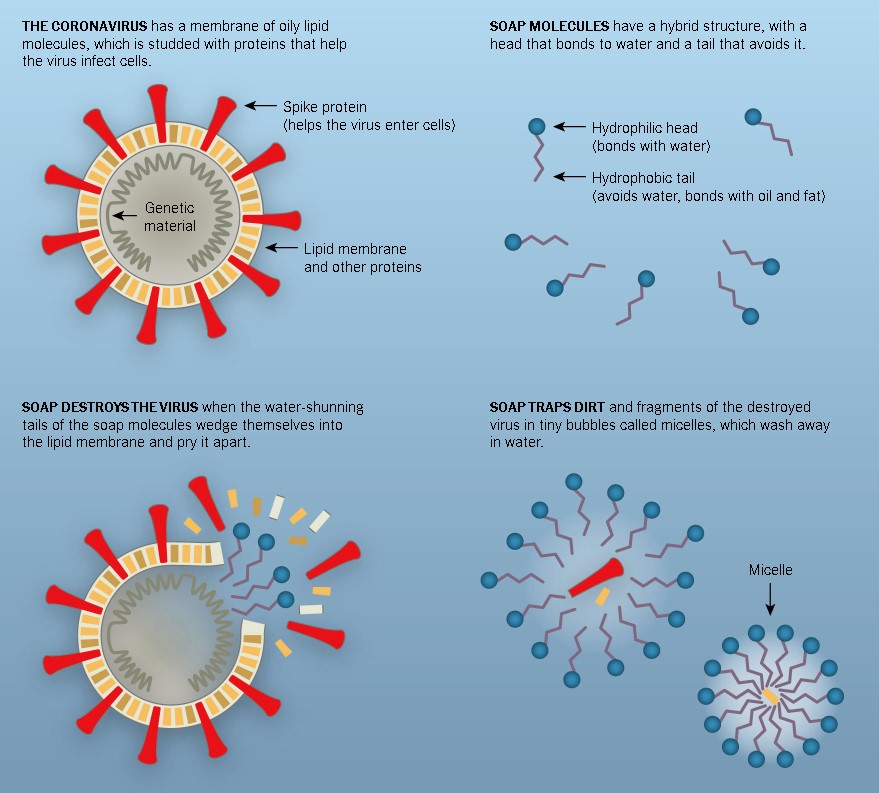

Soap is a common term for amphiphile. An amphiphile is a chemical compound consists of two opposite ends. One end of an amphiphile is water-loving, we called that the hydrophilic head. The other part of an amphiphile is the hydrophobic tail, which is fat-loving. Amphiphiles are also called surfactants.

Surfactants are one of the most versatile compounds in the chemical industry. They are used as cleaning, foaming, emulsifying agents in many products. For example, our everyday detergents, soaps, paints, fabric softeners, shampoos, shower gel, etc.

The most common surfactant you can find in many product labels is sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS). Yes, the same SLS found in most shampoos.

How do you tell if a product contains surfactants? The simple way is to see whether you can form bubbles and foams when using a particular cleaning product. If yes, that means there are surfactants present.

History of Soap Making

Credit: MEMO Photographer Rich Wiles

The production of soap or detergents has been around for thousands of years. The earliest record of soap making dates back to around 2800 BC by the Babylonians. The Egyptians documented the process of making soap-like substances in papyrus. Soap making was described by ancient Romans, Greeks, and Chinese. A combination of fat (animal fat or vegetable oil) with alkaline salts or ash creates soap. Back then, humans predominantly use soap for cleaning.

By the 13th century, soap making was industrialized by the Islamic world in the Middle East. Soap was even exported to Europe. Soapmaking was adopted in Medieval Europe.

In the late 18th century, soaps were manufactured at an industrial scale and became widely available. Advertising campaigns helped for soap promoted the role of hygiene in reducing germs.

But it wasn’t until the 19th century, that liquid soap was invented by the same company that brought us Palmolive. Today, we use soap or detergent in many applications, particularly for cleaning.

The word soap comes from the word sapo, which is Latin for soap.

Credit: Tadé

How does soap work?

Whether its artisan hand-made soap or store-bought plain old soap, they all work the same way.

The key is in the dual nature of the amphiphile or surfactant compounds in soap.

Think about what happens when you pour oil and water into the same container. The oil will pool and float at the top. That is because oil and water don’t mix. When you add soap into the mixture, the oil will disperse. The way it works is that the soap molecules act as an emulsifier. Because of both its fat-loving and water-loving properties, soap molecule acts as a bridge between oil and water.

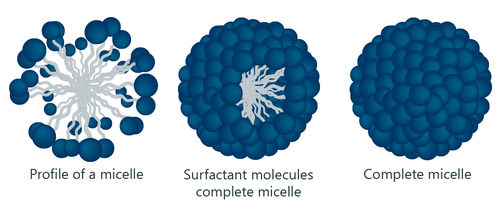

Soap and water, when mixed form micelles, which are tiny clusters of soap molecules with their hydrophobic tails gathered in the center and the hydrophilic heads facing outside. These micelles can trap dirt and grime in their centers. Under running water, the hydrophilic parts are attracted to water, taking the soap and grime with it.

Think about when you are cleaning a greasy pan. It is hard to get rid of the grease with just water. That is because water cannot bond with grease. But with some dishwashing soap, light scrubbing and rinsing with water, voila! You get a clean pan.

How does soap work against coronavirus?

Now we know how soap works, how does soap work against coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2?

It is simple. Coronaviruses are just like the grease on a dirty pan.

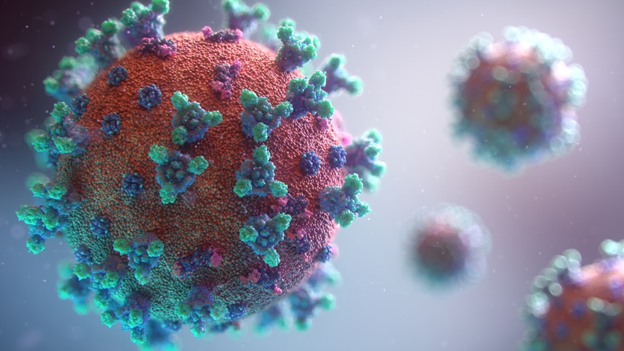

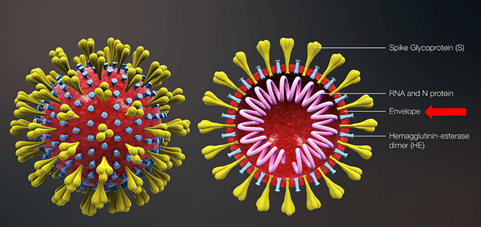

coronaviruses are enveloped viruses with a layer of lipid membrane on the outside. They can stick to the oils and grime on our hands. Water alone is not very effective in removing them from our hands. Similarly, coronavirus can remain on surfaces like door handles, tables, keyboards, etc.

When you wash your hands with soap and water, just like the oil and grime, the viruses get wrapped up and carried away under running water. It is important to rub and cover all surfaces. That way you can make sure the viruses and other germs on your hands are adequately exposed to soap molecules.

Soap also kills coronavirus

The internet is divided on whether soap can kill coronavirus. Soap originally thought only capable of removing the viruses can actually kill them. The key to how this works is in the viruses’ structures.

In the previous post, we discussed the structure of viruses. The envelopes of viruses are made up of lipid membranes just like our cell membranes.

The membrane consists of phospholipids that are amphiphilic like soap molecules. These lipids are held together by weak glue-like bonds with the hydrophobic tails facing each other in the middle of the bilayer.

Credit

When you are washing your hands, you are exposing viruses and germs on your hands to soap molecules. The hydrophobic tails of soap molecules are attracted to the fatty component of the viruses’ lipid layers.

At the same time, the tails are being repelled by water. In the process, their tails wedge themselves into the lipid layer of the virus envelope, disrupting the structure stability.

When you have enough soap molecule-lipid interactions, the structure ruptures exposing the other contents of the virus (protein and genetic information). Viruses fall apart like a house of cards rendering them inactive. Inactive viruses are not capable of infecting host cells. Soap molecules then come in and surround these pieces of viral components. And when you rinse your hands, water washes away the broken parts of viruses. And down the drain, they go.

Handwashing over hand sanitizer

Although alcohol in hand sanitizers can kill viruses, you need to use an adequate amount. Also, if your hands are greasy, sweaty or wet, hand sanitizers will not work well. Of course, hand sanitizer is useful in unideal situations. But washing your hands with soap and water is still the best way.

The catch is that all this takes time. That’s why you need to wash your hands for at least 20 seconds. With soap and friction from rubbing your hands together, you are ensuring maximum exposure of soap molecules to all the germs and viruses on your hands.