In Vaccine series Part 1, we talked about the early history of inoculation and explored the history of smallpox.

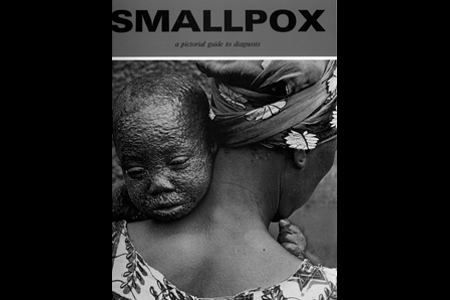

Smallpox was a devastating disease caused by the variola virus. It had claimed countless fatalities throughout human history. Outbreaks of smallpox ravaged across all continents.

In the early days, inoculation or variolation was the best method in inducing immunity against smallpox. However, the major flaw of variolation was that the person would become a carrier of the disease and infect others during the mild infection stages following variolation. Variolation could also trigger more severe infections and even death.

It wasn’t until the end of the 18th century, that a British surgeon and physician Edward Jenner would make scientific advances, which contributed to the basis for vaccination.

The Biography of Edward Jenner

Born in 1749 in the village of Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England, Edward Jenner was the song of a country vicar. Orphaned at the age of five, young Edward went to live with his older brother.

At the age of only 14, he received a seven-year training and apprenticeship under Mr. Daniel Ludlow at Chipping Sodbury, Gloucestershire. After that, in 1770, he moved to London and pursued medical training at St. George’s hospital under Dr. John Hunter, a famous surgeon.

After completing his training in 1772, Edward Jenner returned to his hometown, Berkeley and established his own local medical practice at the age of 23. Throughout his life, he would have established other medical practices in London and Cheltenham, but Jenner spent most of his career in his native town.

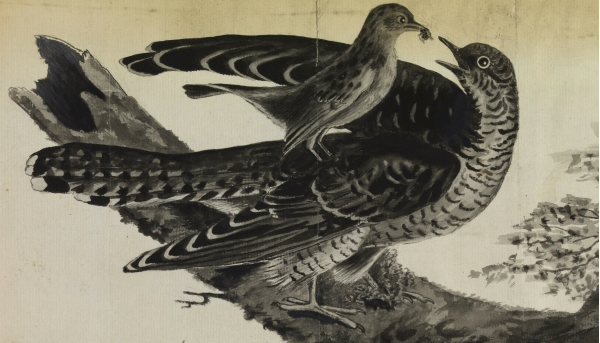

Jenner was a man of many interests. Not only was he interested in medicine and human biology, but he also had a lifelong curiosity in natural science. He studied geology, poetry, and natural history. He even built and launched his own hydrogen balloon. His interest in zoology led him to conduct studies and published a paper on the cuckoo.

During Jenner’s time, smallpox was a deadly disease feared upon by the Britons. At Jenner’s rural practice, he performed variolation on his patients.

He himself was variolated when he was only 8 years old. Most of his patients were from an agricultural community, they were mostly farmers.

In 1788, an outbreak of smallpox swept through his town, and Jenner observed that most of his patients who worked with cattle such as the milkmaids did not get smallpox. These patients were found to had undergone a disease called the Cow Pox through their close work with cattle.

Cowpox is a viral skin infection caused by the cowpox virus. The cowpox virus is a member of the Orthopoxvirus family, the same as the smallpox variola virus. Cowpox virus is zoonotic. It is transferable between species, for example from cows to humans.

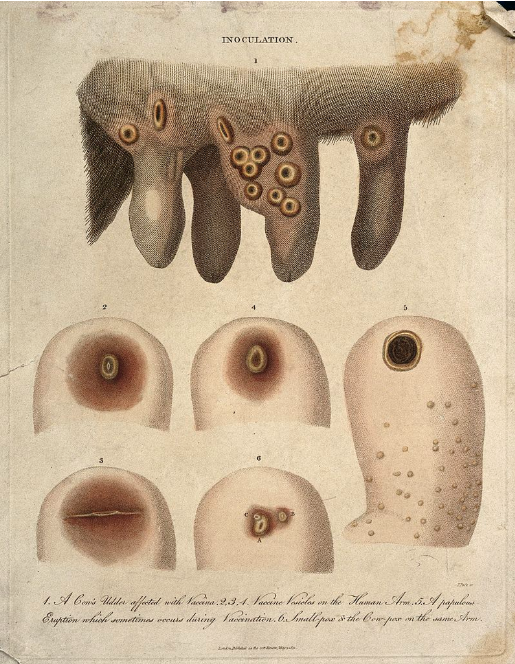

Milkmaids usually contracted cowpox from coming into contact with infected cows. During cowpox infection, they would feel under the weather for a few days and developed pustules on their hands. But the infection was mild, and they would recover quickly.

Jenner’s experiment

National Library of Medicine

In 1796, Jenner took the first bold step in a series of experiments that would lead to his method of vaccination. On May 14th, 1796, Jenner extracted pus from the sores of a woman named Sarah Nelmes who was infected with cowpox. He used the extracted pus and inoculated his gardener’s 8-year old son, James Phillips.

Jenner hypothesized that variolation using cowpox pus would protect the person from smallpox. Young James developed a fever and mild infection after and quickly recovered. Six weeks later, Jenner variolated the boy again, this time with the smallpox virus as per usual variolation practice. James did not develop any symptoms.

Jenner repeated the variolation subsequently and to Jenner’s anticipations, James did not develop smallpox on any of the occasions. Jenner repeated the same experiment on 22 other people. All of them inoculated with cowpox virus recovered and were protected from smallpox infections.

Jenner’s Publication

Jenner submitted a short communication on his experiments and observations to the Royal Society in 1797. However, his paper was rejected as he couldn’t explain why his method worked.

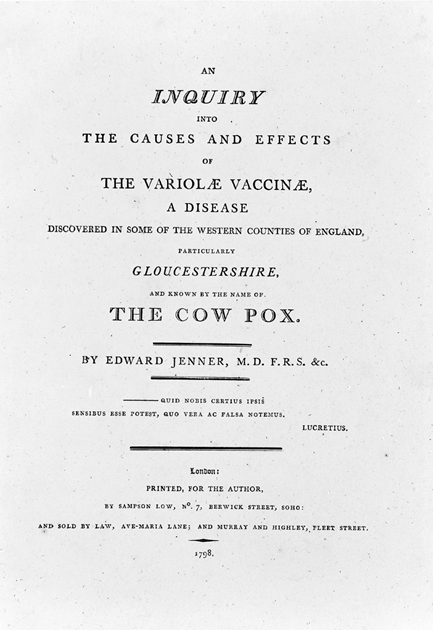

Then in 1798, Jenner published his findings plus more case studies in a booklet, entitled ‘An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox ‘.

Jenner coined the term ‘vaccine’, from the Latin word for cow ‘vacca’. Jenner called his method of variolation with cowpox virus ‘vaccination’.

Opposition to Vaccination

Jenner’s discovery of a new vaccination method against smallpox was met with much ridicule and opposition. The medical communities deliberated Jenner’s findings at length and it wasn’t until decades later that vaccination was widely accepted.

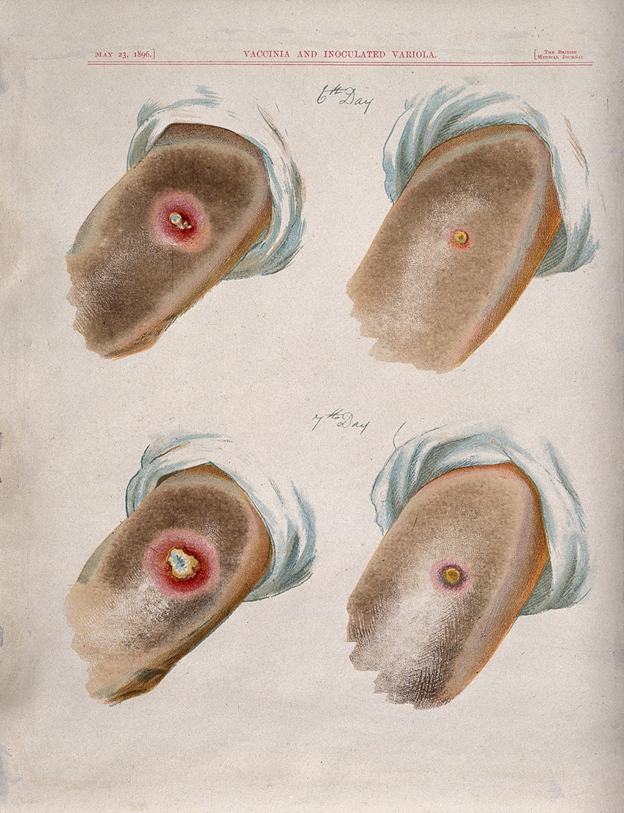

The opposition of Jenner’s method claimed it was ungodly and foul to inoculate humans with virulent materials from diseased animals. Criticisms escalated when poorly trained practitioners carried out Jenner’s method. Jenner’s method emphasized on using less virulent materials from seven-day-old cowpox blisters. These poorly trained practitioners who did not practice Jenner’s method with the same precautions ended up spreading the disease rather than containing it.

Jenner’s emphasis on using less virulent materials would later become vital for tackling other diseases. It was later discovered that vaccine can be developed using weaker

Medical practitioners at the time were big supporters of variolation and did not want Jenner to succeed.

Despite much opposition, Jenner’s discovery became popular as vaccination offered protection against smallpox and the procedure was safer than variolation. Vaccination was gradually implemented and became widespread throughout Europe.

In 1805, Napoleon Bonaparte ordered his entire army to be vaccinated. The Spanish government even brought vaccination to the Americas, China, and the Philippines during a philanthropic mission. In 1840, variolation was banned and vaccination was made available for everyone in Britain free of charge.

Jenner’s Legacy

Jenner’s discovery and vaccination method were recognized worldwide. He received many honors. In 1802, Jenner received a sum of £10,000 from the British Parliament and £20,000 more than five years later. The awards were considered a colossal sum for the time.

Despite all the glory and success, Jenner gradually withdrew from the limelight and returned to his rural medical practice in his hometown. He passed away on the 26th of January 1823. His death was caused by a massive stroke. He was 73 years old.

Today, you can see erected statues of Edward Jenner as far afield as Tokyo. A statue of Edward Jenner can be seen in Kensington Gardens, London.

Perhaps the true legacy of Edward Jenner was his contribution to the works of scientists many years later. His research laid the foundations for the works of scientists like Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur. Together, the works of these early revolutionaries led to the discoveries of new diseases and vaccines against them.

Smallpox Eradication Program

Credit: WHO

Since its establishment after World War II, the World Health Organization (WHO) made it an international agenda to eradicate smallpox. A resolution to eradicate smallpox globally was passed by the governing body of WHO.

In the beginning, the program lacked funding and resources. Although smallpox has been eliminated in North America by 1952 and in Europe by 1953, smallpox was still widespread in endemic countries in South America, Africa, and Asia.

Credit: WHO

It was not until 1967, that the WHO launched the Intensified Eradication Program with increased funding and efforts. More vaccines were produced and administered. The program made significant progress. By 1971, South America was rid of smallpox. In the following years, smallpox was eradicated in Asia and eventually Africa.

On May 8, 1980, WHO declared that the world is rid of smallpox. The annihilation of smallpox is one of the biggest public health achievements in human history.

Credit: WHO

The last known case of smallpox occurred in 1978 in Birmingham Medical School, England. The last victim contracted smallpox either by airborne route or direct contact with smallpox virus in a building where smallpox research was being conducted.

Following the incident, only four countries were holding stocks of smallpox variola virus. They are the U.S., England, Russia and South Africa. By 1984, South Africa and England had either destroyed or transferred their remaining stocks of variola virus.

Now, there are only two official locations for the storage of smallpox virus: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology in Koltsovo, Russia.

These two locations are under the close supervision of the CDC and WHO. The remaining samples are reserved for research. WHO called for the remaining samples to be destroyed.

Credit: WHO

The debate is ongoing. Some scientists have argued that the stocks may be useful in virology research and new vaccine development. However, some worry that the disease could re-emerge or be used as a bio-weapon.

Regardless, the world is a safer place today without any outbreaks of smallpox.

Jenner’s legacy lives on. The world is a better place today thanks to his devotion to vaccination research and the promotion of his methods.

References:

1. Riedel, S. (2005). Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 18(1), 21–25. doi:10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028

2. Smith, K. A. (2011). Edward Jenner and the Small Pox Vaccine. Frontiers in Immunology, 2. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2011.00021

3. WHO smallpox page